This is a brief article I wrote around 2004-2005 that was never published. It is based on a presentation I gave in the Computing Arts stream of the AHA Conference held in Newcastle in 2004. I have decided to publish it here as it explains some of the background and thinking behind the Chinese Australian Historical Images in Australia website (now archived). I have reproduced it here as originally written.

Introduction

A photograph is complex entity (Barthes, 1979; Sontag, 1979; Tagg, 1988). In its broadest definitions it encompasses both the original negative when the photograph is taken but also the many prints and copies that can subsequently made through time. It also includes the full range of photographic formats from the early daguerreotypes, ambrotypes and tintypes through to roll film, colour prints and digital photographs (Clarke, 1997, p.19). Multiple copies of a photograph might exist. Each will vary slightly, some more than others, depending on nature of the copy made. This might relate to whether the image has been cropped or enlarged, the type of printing style adopted or the printing materials used (Sassoon, 1998, p.7).

Like written documents, photographs are representations of the world and are open to broad interpretation. Edwards describes them as having an ‘unprocessed’ or ‘raw’ nature and Pinney that they are ‘worrying’ because they have ‘too many meanings’ (Edwards, 2001, p.5; Pinney, 1992, p.27). They are more than simply illustrations accompanying text. Increasingly photographs are being used in more complex ways, particularly in research in the fields of history, art history and anthropology (see for example Edwards, 2001; eds Pinney et al., 2003; Ennis, 2000; Lydon, 2000; Reeder, 1995).

The databases we create to assist in the use of photographs need to respond to these needs. This paper examines some of the challenges faced when working with historical photographs within a digital online database. It explores this through a discussion of the dilemmas posed by a photograph of a stage coach loaded with apparently Chinese passengers for the Chinese Australian Historical Images in Australia (CHIA) project database.[i]

The CHIA database utilizes a system developed by AUSTEHC called the Online Heritage Resources Manager or OHRM (McCarthy, 1999a; McCarthy, 1999b; McCarthy, 1999c; Evans, 1999; AUSTEHC, 2004). One of the objectives of the project is to extend the ORHM so it can incorporate historical pictorial images as more than simply illustrations. Historical images of people of Chinese heritage in Australia between 1850 and 1950 provide the data for the project. CHIA draws substantially on the collection of the Museum of Chinese Australian History in Melbourne for its data, but also other collections including those available on-line. In this respect it is similar to PictureAustralia which draws together Australian images in multiple archival collections (National Library of Australia, 2002). At this stage the database is still under development and is not available for public access.

The photograph and its dilemmas for databases

Copies of copies

You may be familiar with the photograph under discussion (see Figure 1). This photographic image has been well, some might say, over used in many published histories, particularly photographic histories of the Victorian goldfields. Many copies of it exist in different formats including: copy-prints, glass negatives, postcards and published prints.

At some point a photographer stood in front of the coach and took the photograph and an original negative was produced.[ii] From this time onward numerous prints may have been taken from that original negative. Photographic copies may have subsequently been taken from either or both the original negative or these original prints. A new negative would have been created from each of these copies. Again further copies could then be made. Photographic prints and negatives can also be reproduced in published form. Any one of these originals or copies may end up in an archive or publication. My research has not uncovered the original negative or I believe any of the original prints of this photograph. However without doing a comprehensive search I have located well over a dozen copies of this photograph published in books and held in different archives. The earliest copies were made in c1900-1920, 1931 and 1946.[iii] The State Library of Victoria holds two of these.

The history of ownership and usage of this photograph helps to reveal the role that the photograph has played in society through time. With each use photographic images acquire different meanings. Analysis of these types of photographic histories has been particularly fruitful for scholars of colonialism who have explored the relationship between colonial photography and the forces of domination, repression and resistance (Edwards, 2001, p.3). It is therefore important that information about the different copies of a photographic image is preserved. It is particularly useful if different versions of the same photographic image are collated together. This is not currently done by major image databases in Australia.

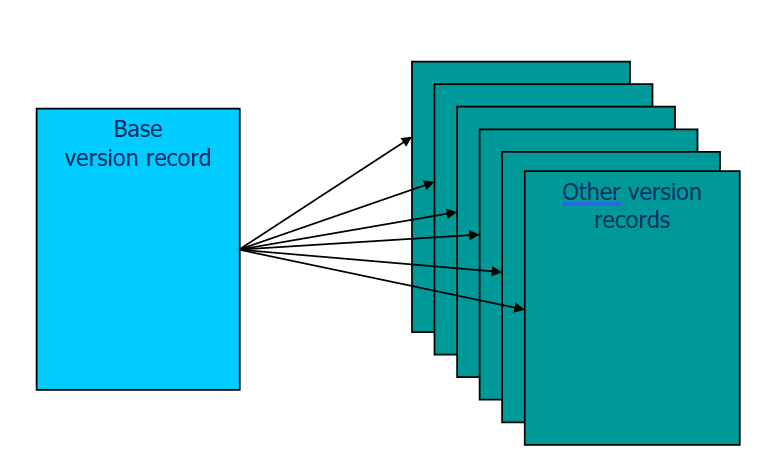

The CHIA database incorporates information about photographs held in numerous archival collections and publications. In the initial version of CHIA database the different versions of the Cobb and Co photograph were dealt with by selecting an arbitrary version of a photograph (the one with the most information about it) as a base record. Information about the different versions and the archive or publication they belonged to were appended to that base record (see Figure 2). Any number of ‘versions’ could be linked to this ‘base’ record. Our system parallels the Functional Requirements for Bibliographic Records model which is developed for bibliographical materials that have numerous manifestations and expressions (for example see Hickey et al, 2002).

It quickly became clear that if every version of a photograph was given a separate version record data entry would become unmanageable. Often archives will hold a number of copies of a single that photograph that have been derived from a single copy. For example the Chinese Museum holds a photographic copy print and a negative both taken from copies held by the State Library of Victoria. Separate version records were not created for these two versions of the photograph because there was seen to be little value for users by doing this. Subjective decisions were therefore made at the data entry level as to how many versions might be created for a single archive.

Cropping

Another complexity raised by the Cobb and Co coach example is the cropping of some copies of the photograph. Sometimes cropping can substantially change the nature and meaning of the photograph. Such information is particularly useful for researchers as it illuminates the ways photographs have been manipulated by those who use them. For example the Mitchell library holds a photomontage taken by Kerry and Co. It is composed of a number of separate photographs of Quong Tart and his home and family arranged with decorative flora and which has then been photographed.[iv] The montage itself is a single photograph but the individual photographs within the montage also exist as independent photographs.[v] This means a decision is needed about when a cropped picture becomes a different picture, justifying a new record. In this particular example two separate ‘base’ records were created and a relationship created between the two.

Cropped versions of the Cobb and Co coach photograph excluded a part of a building on the left-hand side and/or two apparently non-Chinese figures on the right-hand side. Although this has important implications for identifying and using the photograph the cropped versions of the photograph were not considered to be substantially different from each other. All cropped versions of the Cobb and Co coach photograph were therefore treated as simply ‘versions’ of the ‘base’ photograph and information was added to the text field about the nature of the cropping.

Our initial database design was successful when dealing with photographs as physical objects. However as discussed previously, photographs are also subjective representations, open to interpretation and re-interpretation in different contexts.[vi] We realized that just as others had interpreted the photograph in different ways we also wanted to be able to do so. The database therefore required slight modification. The complications arising from the distinction between a photograph as an object verses a representation is important as it is not adequately tackled by many Australian image databases and yet is fundamental to historical photographic research.

Object verses representation

It is useful to begin by thinking of a photograph, whether an original negative or photographic copy, as an object. As an object, a photograph is the product of a technical and chemical process. It was created by someone, for someone, of someone or something. Once the object comes into existence it begins to develop its own history and acquire new meanings through time. It can be used in different ways by different people, reused, stored in archives, owned by different people, travel to different places, be copied, be damaged, destroyed, restored, enhanced or modified. All this is part of the history of the object. The object’s existence and role in our society through time tells us something about our society and its history.

Dublin Core metadata, initially devised for bibliographic objects, is also used in modified form by most major archives to describe and define photographic objects (Weibel et al., 1997; Dublin Metacore Initiative, 1995-2004). In simplistic terms DC metadata standards derive from questions such as:

- how big is it? (physical dimensions)

- what is it made of? (physical composition)

- who made it? (creator/s)

- when was it made? (creation date)

- where was it made? (creation place)

- where is it located now? (identifying code/archive)

- if it belongs to a larger group of objects what is this collection called? (collection)

- what can be done with it? (rights)

We might not know the answers to all these questions for a given photograph but the answer to them is unambiguous. Two obvious fields have not been included in this list: ‘title’ and ‘description’. This is because I find them to be problematic. Unlike these other fields ‘title’ and ‘description’ do not inherently relate to the object itself. They are imposed on the object by those who created it or who have subsequently used it based on their interpretation of what the photograph represents.

Describing the content of a photograph is a subjective process. It is the viewer, influenced by historical and cultural processes, who gives meaning to a photograph – without whom a photograph is simply discoloured paper (Tagg, 1988, pp.2-3). As Barthes has noted it is impossible to describe a photograph in any way that does not necessarily reduce the depth of what is being depicted (Barthes, 1977, p.8). The same photograph can also represent different things to different individuals (Barthes, 1977, p.46; Tagg, 1988, pp.1-4). For example when I, as a Chinese Australian historian, look at this photograph I see a group of people who appear to be Chinese on a coach. I am interested to different things to Geoff Powell, the curator at the Cobb and Co coach Museum who I’m sure is more interested in the coach than its passengers. The photograph will also be viewed differently through time. How might the photographer who took the photograph have chosen to title and describe it? Was it simply a photograph of a coach loaded with ‘Chinamen’ or ‘Celestials’? Or indeed how might one of the passengers have described the resultant photograph, or one of their descendants?[vii] What might they be able to say about the clothing worn, the identity of the coaches passengers and their place of origin in China.

These differing interpretations are particularly relevant to Chinese-Australian history where the perspectives of the Chinese-Australian subjects in photographs, such as the passengers in the Cobb and Co coach photograph, are becoming increasingly valued. It has only been relatively recently that historians in Australia have begun to try and obtain more sophisticated understandings of who the ‘Chinese’ who came to Australia were. Increasingly researchers are looking to write histories that view Chinese on their own terms rather than simplistically through colonial eyes (Cushman 1984, McKeown ,1994). This has resulted in a much greater understanding of the importance to Chinese-Australian history of clan and village of origin, organisation and political party affiliations, social status within Chinese-Australian networks and of course the lives of the individuals themselves.

Captions and text associated with photographs help to focus the viewer’s gaze and understanding of the photograph but they also restrict it (Barthes, 1977, p.25). It is therefore valuable for databases to provide the different titles and descriptions of photographs as it alerts users to the different meanings a photograph might have. It also helps us to understand how the photograph has been and is being used and the meanings that can be ascribed to it. Titles and descriptions are also necessary for practical considerations. It is difficult to discuss a photograph without giving it a name. Our project found that the titles and descriptions provided by others did not always suit our purposes. For example the CHIA database is filled with photographs of Chinese people it is therefore not useful for us for searching purposes to have titles that begin with the word ‘Chinese’. We are not interested in reinforcing the use of offensive terms in our main titles (although this information may be recorded in other parts of the database).

Once we see ‘title’ and ‘description’ as part of defining the content of the photograph rather than its nature as an object there are other fields we might also want to add, such as the date and location of the event being represented. When dealing with an original or close to original copy of the photograph these fields may be the same as the date and location the photographic object was created. However this is often not the case. For example the copy of the Cobb and Co coach photograph held by the Chinese Museum was made by the State Library of Victoria in Melbourne some time in the 1980s.

In 1998 Joanne Sassoon voiced concerns that archival institutions were too focused on the photograph’s content when managing photographic collections and saw the digitization of photographs as a replacement of the photographic objects themselves, disregarding the loss of meaning contained within the materiality and physical context of the photographic object (Sassoon, 1998). I believe many of the major image databases currently being developed (and those that are evolving) are attempting to address these concerns. There is now a much greater awareness of photographs as objects to the point that image databases now suffer because of the tension created by the cataloguing and description of photographs as objects and the demands of most users who I would argue are more interested in what is being represented in the photograph.

Take for example, ‘Stage coach laden with luggage and many Chinese people en rout to the gold fields’, one of the copies of the State Library of Victoria’s on-line catalogue entry for the Cobb and Co coach photograph.[viii] As a user I might be looking for nineteenth-century photographic representations of Chinese. I won’t find this photograph because the date information in the record relates to the date the copy of this photograph was created not when the original photograph was taken. There is a comment in the ‘notes’ field of the record that the Library print is a copy of an earlier photograph but we have no estimation of the period when the photograph might have been taken. This is dealt with differently in the other copy of this photograph that the State Library of Victoria holds which provides an 1855 to 1931 date range for searching purposes but lists July 20, 1931 as the date of creation.[ix]

It is often difficult to tell whether date information provided relates to the date of the photographic object or the date of the information being represented in the photograph. Sometimes there are inconsistencies within a single database. Difficulties dating photographs, particularly the content of photographic copies, no doubt contribute to this problem (Frost, c1991; Barrie, 2002, p.viii). Added to this confusion is the fact that information about a photograph becomes lost and distorted through time.

So I argue, not that photographs be catalogued as anything other than objects, nor that information about the photograph as an object is unimportant, but simply that we need to ensure that our ways of searching for photographs make more explicit the differences between characteristics describing the photographic object and those describing what is represented in the photograph.

The Cobb & Co dilemmas

The Cobb and Co coach photograph is a wonderful example of how wildly variant information about the content of a photograph can be (State Library of Victoria; Museum of Chinese Australian History; Bendigo Golden Dragon Museum; Creswick Historical Museum; Peppin Heritage Centre; Hornadge, 1976; Rolls, 1992; Hocking, 2000; Cato, 1977; Flett, 1977; Hocking, 1994; Sierp, 1972; Reid et al., 1989; Austin, 1977). The photograph has been variously described as showing Chinese miners off to the gold diggings or more specifically off to the Victorian gold diggings. Others claim the miners are leaving Castlemaine, Newstead or Ballarat; that they are heading to Castlemaine, Fiddler’s Creek or possibly Maryborough. The passengers on the coach have also been described as being labourers setting out from Deniliquin on their way to Coree Station near Jerilderie, New South Wales or strike breakers on their way to Clunes, Victoria. Various dates have been assigned to it, some as early as the 1850s, others 1855, 1865, 1871, 1873 or even 1883.

My interpretation of the content of this photograph is different again to any single interpretation. Four close to original versions of this photograph are extant. The State Library of Victoria holds a glass negative of a print made c1900-1920 and gelatin silver copy of a print loaned in 1931. The Creswick Historical Society holds two postcard prints that were made by E.J. Semmens from an original loaned to him possibly by E. Dowie in 1946. A private collector in Newstead also holds another early postcard print copy of this photograph.

Most printed copies of the photograph in other collections have been made from one of the State Library of Victoria copies of the photograph. These can be identified by large ‘scratches’ or ‘cracks’ running from the top left hand corner to the bottom right hand corner and more severe cropping than the Creswick Historical Society version. Captions used tend to loosely follow information available at the State Library of Victoria, however in some cases the photograph has clearly been appropriated for other illustrative purposes.

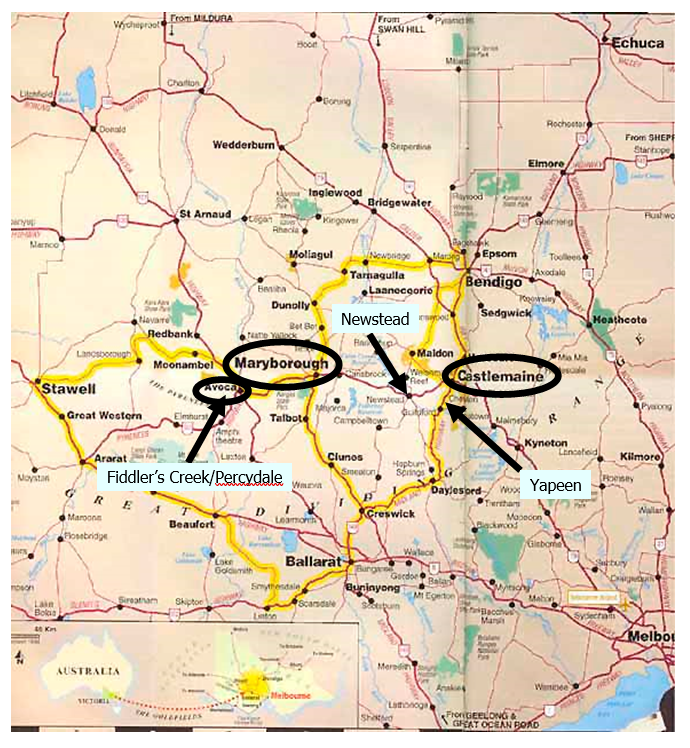

The overlapping nature of quite specific details about the contents of the photographic image suggests it is of a group of miners, probably Chinese, taken in Newstead on their way to the gold rushes at Percydale or possibly Maryborough c1865-1871 (see Figure 3). James Flett suggests the photograph, based on a private letter, was taken in Newstead, near Yapeen which he claims contained the largest Chinese community in Victoria at the time (Flett, 1977, p.89). The letter also names the driver of the coach. Castlemaine is the nearest large town to Newstead. Information associated with one of the State Library of Victoria copies states that the photograph was taken in Castlemaine.[x] A copy of the photograph belonging to a member of the Newstead Historical Society is described as being of Chinese miners going from Newstead to Percydale (previously Fiddler’s Creek), just west of Avoca, c1871.[xi] Annotations made by E.J. Semmens on the back of his copies state the photograph is of Chinese on their way to Fiddlers Creek (Percydale) in 1865.[xii] Maryborough is noted in brackets. A trip from Newstead to Percydale would pass through Maryborough.[xiii]

(Base map courtesy: Finders, ‘Goldfields tourist area map’, http://www.finders.com.au)

My c1865-1871 time frame estimate is based on information associated with these early copies of the photograph and also falls within the expected date of the photograph based on the design of the Cobb and Co coach. Geoff Powell of the Cobb and Co Museum in Toowoomba suggests the original photograph was taken some time in the 1850s-1860s based on the the style of coach and an expected ten to twelve-year average coach life at that time.[xiv]

While this interpretation of the subject matter of the Cobb and Co coach photograph seems a likely one it is in no way certain. One of the advantages of working within a digital environment is that if another version of the photograph is found or further information obtained the database can be updated.

The database and html output

The initial database design the CHIA project developed (see Figure 2) did not require substantial revision. Rather than being used for an arbitrary version of the photograph, the base record or fields in the main record for a photograph, was changed to store the CHIA project interpretation of the image. The versions records then record the physical manifestations or version of the photograph including information about the archive in which it is held. This is more easily discussed through the page of html output that is drawn from the database about a photograph.

The top section of the page provides the CHIA interpretation of the photographic image. This includes: a title, a description of the contents of the photograph, an estimated date (or date range) of subject matter in the photograph, the place shown in the photograph and an interpretative description of the relationship of the various versions of the photograph. This interpretive field is useful given the confusion created by so many versions of the image. This field also provides an opportunity to make transparent decisions that have been made about the content of the photograph.

At the top right hand corner of the page is a digital thumbnail of the photograph. This is selected from one of the versions of the photograph available. Clicking on the thumbnail takes the user to a larger version of the image. This larger version might exist on another website or within the CHIA database.

Further down the page various versions of the image are described. This information is provided by the archive or publication where the photograph is physically located and might include: title, description, physical description, control or accession number, name of the archival source or publication citation, provenance and rights to the photograph.

By clicking on version titles that are hot-linked the user is taken to the original source of that version of the image if it is available on the web. By utilizing the interconnectivity of the web users are led directly to the source of information provided about the photograph by the archive holding it. This means for example that if an archive updates their information about a picture and we have not had a chance to update our version of their information then at least the user can discover the update themselves.

Archive names in the version list are hyper-text links that take the user to a list of other Chinese-Australian related images held in their collection. There is a small ‘details’ hotlink next to the archive/publication name that leads users to more information about the archive or publication itself.

While one visual copy of the photograph is used as the main image for users of the database. Digital copies of each of the versions, where available on the web or held by the CHIA project, can also be viewed through a link associated with each version. Where possible this includes the backs of photographs. It is relatively common for photographs to have important information on their backs including illustrations as well as text. Photographic studios for example often advertised on the back of nineteenth-century cabinet cards. In these instances it is important photographs are treated more like the three-dimensional objects they are.

At the very bottom of the page about a particular image version is a list of ‘related entries’. These ‘related entries’ might also be described as ‘descriptive keywords’. These provide contextual information about subject matter contained in the photograph and also provide a gateway to further images about that subject matter (McCarthy, 1999b).

Conclusion

In summary the complexities the project has been grappling with are as follows:

- Multiple versions of photographs held in different archives and published in different publications;

- Versions with different physical characteristics, including slightly different croppings;

- No ‘original’ negative or print extant;

- Different interpretations of the photograph content; and

- Distortion and loss of information about photograph through time

The CHIA project is trying to tackle these issues while at the same time keeping data-entry manageable and database output comprehensible. This is one of our biggest challenges, though a fundamental one to most database projects (Galloway, 2004).

In creating solutions to these challenges the CHIA project has found it useful to distinguish between a photograph as object and as representation. This has not been explicitly done in most Australian online image databases. This means users will be able to search for information about what is being represented in the photograph, such as when and where the event being represented in the photograph occurred as well as the physical characteristics of the photograph. The physical manifestations of any given photographic representation, such as prints, negatives, digital and published copies etc are then collated and viewed together. This encourages and makes it much easier to unravel the sometimes complex provenances and meanings attached to photographs.

Bibliography

AUSTEHC (2003). Online Heritage Resource Manager (OHRM), AUSTEHC website. http://www.austehc.unimelb.eud.au/ohrm/ (accessed 19 August 2004).

Austin, K.A. (1977). A Pictorial History of Cobb & Co.: The Coaching Age in Australia, 1854-1924. Adelaide: Rigby.

Barrie, S. (2002). Australians Behind the Camera: Directory of Early Australian Photographers, 1841-1945. Booval, Queensland: S.Barrie.

Barthes, R. (1979). Image, Music, Text. Glasgow: Fontana/Collins.

Cato, J. (1977, 2nd edn). The Story of the Camera in Australia. Melbourne: Institute of Australian Photography.

Clarke, G. (1997). The Photograph. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press.

Cushman, J. (1984), ‘A “Colonial Casualty”: The Chinese Community in Australian Historiography. Asian Studies Association of Australia Journal, April 7(3).

Driessens, J. (2004). Relating to Photographs. In Pinney, C. and Peterson, N. (eds), Photography’s Other Histories. Durham and London: Duke University Press.

Dublin Metacore Initiative (1995-2004). Using Dublin Core, Dublin Metacore website. http://dublincore.org/documents/usageguide/elements.shtml (accessed 4 August 2004).

Edwards, E. (2001). Raw Histories: Photographs, Anthropology and Museums. Oxford and New York: Berg.

Ennis, H. (2000). Mirror with a Memory: Photographic Portraiture in Australia. Canberra, ACT: National Portrait Gallery.

Evans, J. (1999). ‘Exploring Bright Sparcs: creation of a navigable knowledge space’, paper presented at Charting the Information Universe, 13th National Cataloguing Conference, Brisbane, 13-15 October.

Flett, J. (1977). A Pictorial History of the Victorian Goldfields. Adelaide: Rigby Ltd.

Frost, L. (c1991). Dating Family Photos 1850-1920. Essendon, Vic.: L. Frost.

Galloway, E. A. (2004). Imaging Pittsburgh: Creating A Shared Gateway to Digital Image Collections of the Pittsburgh Region, First Monday, .9(5), May. http://firstmonday.org/issues/issue9_5/galloway/index.html (accessed 4 August 2004).

Hickey, T., O’Neill, E.T. and Toves, J. (2002). Experiments with the IFLA Functional Requirements for Bibliographic Records (FRBR), D-Lib Magazine, 8(9), September. http://www.dlib.org/dlib/september02/hickey/09hickey.html (accessed 19 August 2004).

Hocking, G. (2000). To the Diggings!: A Celebration of the 150th Anniversary of the Discovery of Gold in Australia. Port Melbourne: Lothian Books.

Hocking, G. (1994). Castlemaine : From Camp to City 1835-1900, A Pictorial History of Forest Creek and the Mount Alexander Goldfields. Knoxfield, Vic.: Five Mile Press.

Hornadge, B. (1976, 2nd edn). The Yellow Peril: A Squint at Some Australian Attitudes towards Orientals. Dubbo, NSW: Review Publications.

Lydon, J. (2000). Regarding Corranderrk: Photography at Corranderrk Aboriginal Station, Victoria. PhD thesis, Australian National University.

McCarthy, G. (1999a). ‘Engineering Utility: A Visionary Role For Encoded Archival Authority Information In Managing Virtual And Physical Resources’, paper presented at AusWeb99, the Fifth Australian World Wide Web Conference, April. http://ausweb.scu.edu.au/aw99/papers/mccarthy/ (accessed 19 August 2004).

McCarthy, G. (1999b). ‘Heritage and the Internet – Encoding Context Objects: Using Knowledge to Reduce Risks’ paper presented at the Australian Society of Archivists 1999 Conference, Brisbane, July. http://www.archivists.org.au/events/conf99/mccarthy.html (accessed 19 August 2004).

McCarthy, G. (1999c). Utilizing the Web to Build a Network of Archival Authority Record, Janus, 1, pp.96-107.

McKeown, A. (2004). Introduction: The Continuing Reformulation of Chinese Australians. In Couchman, S., Fitzgerald, J. and Macgregor, P. (eds). After the Rush: Regulation, Participation and Chinese Communities in Australia. Special Issue Otherland Literary Journal No.9, November 2004, pp1-9.

National Library of Australia (2002). How PictureAustralia Works, Picture Australia website. http://www.pictureaustralia.org/join.html#works, (accessed 4 August 2004).

Pinney, C. (1992). The Parallel Histories of Anthropology and Photography. In Edwards, E. (ed.). Anthropology and Photography, 1860-1920. New Haven and London: Yale University Press in association with The Royal Anthropological Institute, pp.74-95.

Pinney, C. and Peterson, N. (eds) (2003). Photography’s Other Histories. Durham and London: Duke University Press.

Reeder, W. (1995). The Democratic Image: The Carte-De-Visite in Australia 1859-1874. MLit thesis, Australian National University.

Reid, R., Chisholm, J. & Harris, M. (1989). Ballaarat, GoldenCity. Bacchus Marsh, Vic.: Joval.

Rolls, E. (1992). Sojourners: The Epic Story of China’s Centuries-old Relationship with Australia. Queensland: University of Queensland Press.

Sassoon, J. (1998). Photographic Meaning in the Age of Digital Reproduction, LASIE, 5, December, pp.5-15.

Sierp, A. (1972). Colonial life in Victoria : Fifty Years of Photography, 1855-1905. Adelaide: Rigby.

Sontag, S. (1979). On Photography. Middlesex, UK: Penguin Books.

Tagg, J. (1988). The Burden of Representation: Essays on Photographies and Histories. London: MacMillan Education.

Tsinhnahjinnie, H.J. (2003). When is a Photograph Worth a Thousand Words? In Pinney, C. and Peterson, N. (eds), Photography’s Other Histories. Durham and London: Duke University Press.

Weibel, S. and Miller, E. (1999). Image Description on the Internet: A Summary of the CNI/OCLC Image Metadata Workshop, D-Lib Magazine, January. http://www.dlib.org/dlib/january97/oclc/01weibel.html (accessed 19 August 2004).

Notes

[i] CHIA is a joint Australian Research Council funded project between Asian Studies, La Trobe University, the Museum of Chinese Australian History (Chinese Museum) and the Australian Science and Technology Heritage Centre (AUSTEHC). I am a PhD candidate attached to the project.

[ii] As an ‘original’ print or negative has not been located it is also possible that the original photographic image was created using a direct-image process in which a single positive image is created without the use of a negative. Direct-image processes include daguerreotypes, tintypes and ambrotypes.

[iii] State Library of Victoria picture collection, H352344, H2407 and ‘Chinese folder’, Creswick Historical Society.

[iv] ‘With compliments of Mr & Mrs Quong Tart, 1892, ‘Gallop House’, Ashfield, Sydney N.S.W.’, Mitchell Library picture collection, SV1A/Ashf/2.

[v] For example the photograph of Quong Tart and his family standing in front of their house was published in Illustrated Sydney News, 22 April 1893.

[vi] Clarke, 1997, p.15 discusses photographs as both objects of attention and images of information.

[vii] A body of literature is emerging in both the United States and Australia in which descendants of indigenous people are reclaiming colonial photographs. See for example: Lydon, 2000, pp.264-294; Driessens, 2003, pp.17-22; Tsinhnahjinnie, 2003, pp.40-52.

[viii] ‘Stage coach laden with luggage and many Chinese people en rout to the gold fields’, State Library of Victoria picture collection, H35244.

[ix] ‘Chinese leaving for the diggings, Cobb’s coach, Castlemaine’, State Library of Victoria picture collection, H2407.

[x] ‘Chinese leaving for the diggings, Cobb’s coach, Castlemaine’, State Library of Victoria picture collection, H2407

[xi] Email communication, Dawn Angliss, Newstead Historical Society, 26 May 2004.

[xii] ‘Chinese folder’, Creswick Historical Society.

[xiii] The Cobb and Co route c1863 started in Castlemaine with the arrival of the train from Melbourne and then went to Newstead, Carisbrook, Maryborough, Back Creek, Avoca, Moonambel, Landsborough, Barkly, Red Bank, Evelyn, Ararat, Maldon, Eddington, Dunolly, Tarnagulla and Burnt Creek.

[xiv] Telephone communication, Geoff Powell, Cobb & Co Coach Museum, Toowoomba, 28 May 2003.