Presented by Dr Sophie Couchman at Brought to Light: Darkrooms to glasshouses…, Castlemaine Art Museum, 10 May 2023.

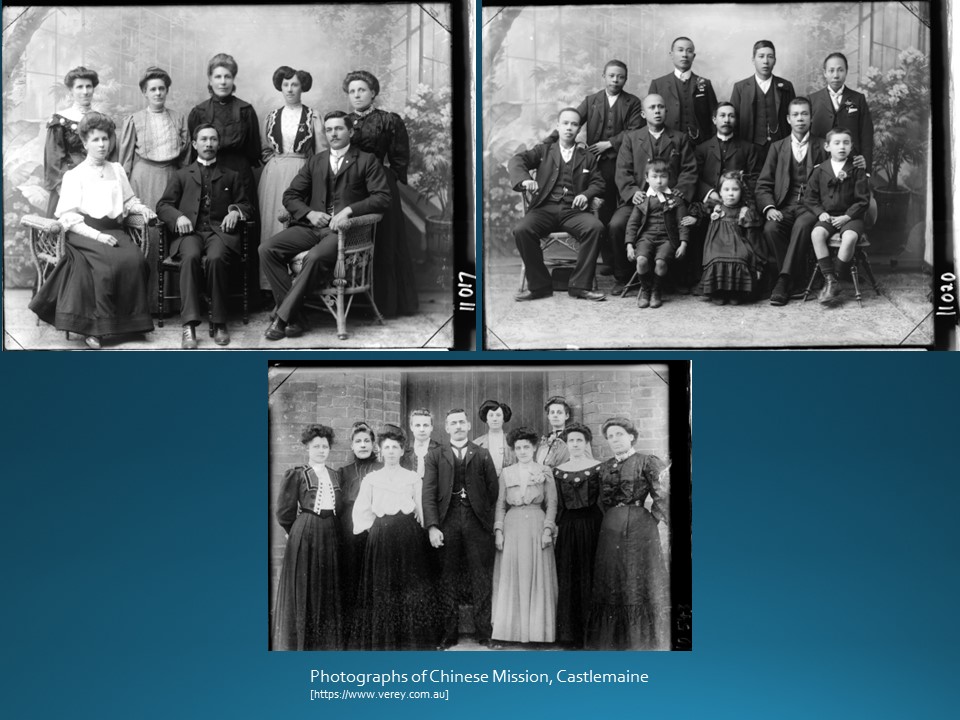

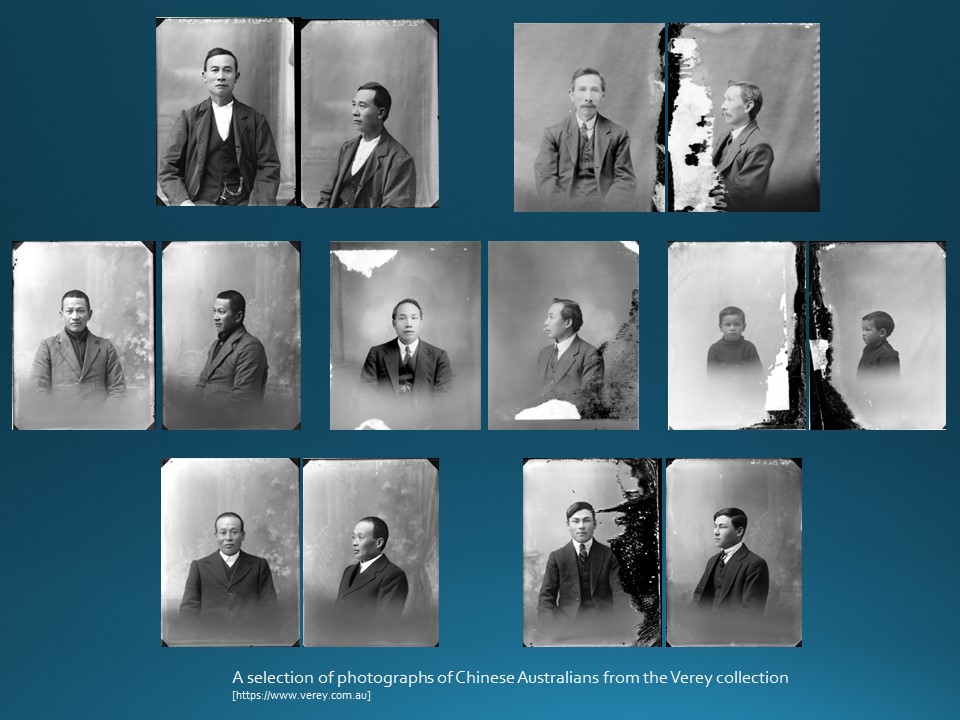

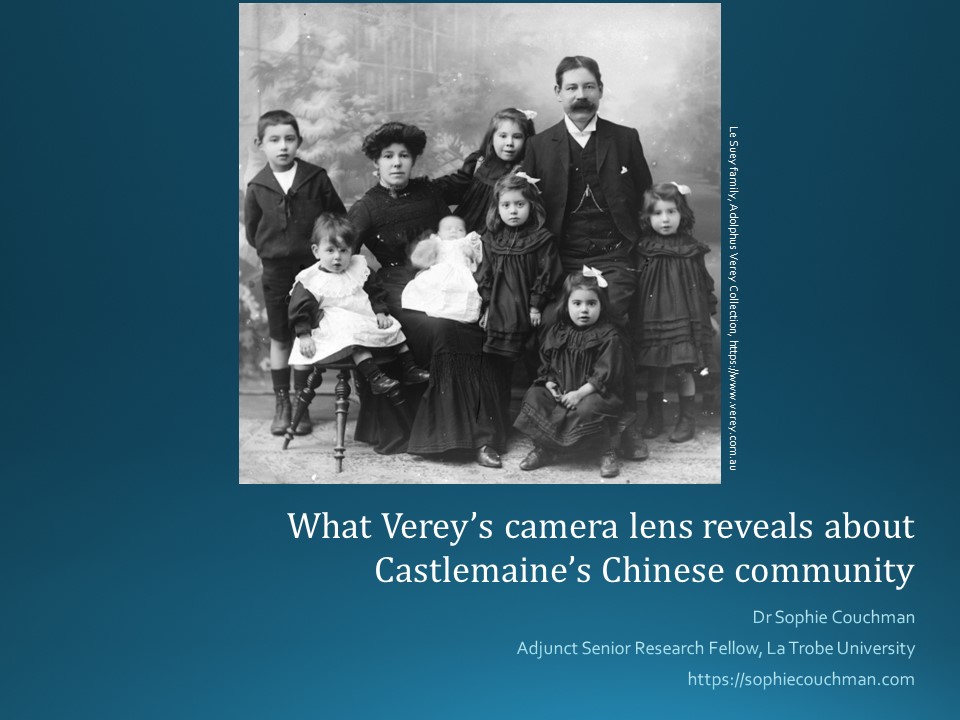

I’d like to start this presentation with a selection of photographs of Chinese Australians from the Verey collection held by Ashley Tracey and searchable online.1 I use the term Chinese Australians to refer to both Chinese immigrants and also people born in Australia with Chinese ancestry.

Unlike today, photographs were a relatively precious commodity in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century when these images were created. They were relatively inexpensive to purchase but still financially out of reach for some and not a decision taken lightly for most.

I’d like to ask you imagine why these individuals might have chosen to go to a photographic studio to have their portrait taken.

Photographic portraits like these were often taken of families, new babies and children, daughters when they came of age and to mark special occasions: anniversaries, weddings, business partnerships and even friendships.

It is likely these portraits of the teachers and students of Castlemaine’s Chinese Mission were taken either to mark the Mission’s Diamond Jubilee celebrations in 1917 or the arrival of Chinese missionary David Gohn in 1906.2 It can be tricky dating photographs by fashions if people don’t keep up with the latest fashions and most of the photographs I’ve been able to accurately date in the collection, were taken in the 1910s and 1920s.

What I wonder are we to make of these follow portraits? Can anyone tell me what these photographs might have been used for? They are certainly familiar to us as identification photographs.

From the late 1890s Chinese Australians who travelled overseas were the only major cohort of Australians systematically photographed for identification purposes outside the prison system.3 Passports with photographic identification were not introduced in Australia until 1915. Immigration restrictions made it virtually impossible to bring family into Australia and so many Chinese men travelled between Australia where they worked and China where their families were.

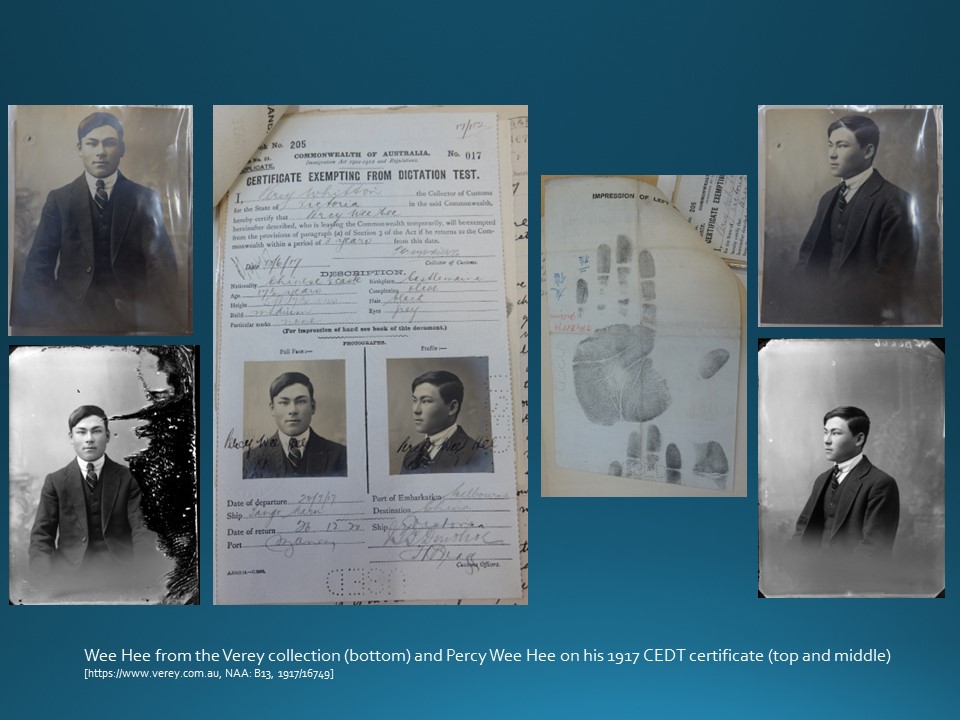

Under the 1901 Immigration Restriction Act, colloquially known as the White Australia Policy, long term Chinese residents needed to provide an identification photograph as part of applying for a certificate, CEDT, that exempted them from a dictation text, when they re-entered Australia. The test designed to be given to any ‘coloured’ arrival considered to be undesirable and was also given to Indian, Afghan and Japanese arrivals. It was not a fair language test and was designed to be failed by those who had to sit it.

The aim was to reduce the size of the Chinese population in Australia which it succeeded in doing. By 1911, according to the population census, Victoria’s Chinese population was around 4,400. This was a drop from a peak during the goldrushes of around 40,000. And by 1933 the population had dropped further to just shy of 2,000 people.

The combination of these two things: use of identification photography for travel and a shrinking Chinese population provides a rich research opportunity. It is possible, with a bit of care, to match the names and photographs in the Verey collection with those on surviving travel and other documentation.

Below you can see documentation related to Wee Hee, better known as Percy Wee Hee. Percy Wee Hee was born and attended school in Castlemaine and worked as a market gardener at Wesley Hill. Here he is aged around 17 ½ years old. His hand and fingerprints were taken as part of the identification process when he travelled. He left Melbourne for Hong Kong on 20 July 1917 on the Tango Maru and returned just under 3 ½ years later landing on 26 December 1920 in Sydney.

In 1908 he applied for another CEDT which he doesn’t seem to have used, although his father did travel then. The photograph Percy Wee Hee supplied at time is still on file. Percy was better known in Bendigo where he lived most of his life, working as a court interpreter.4 He was also a key figure in the organisation of the Chinese section of the Bendigo Easter parade. He died at only thirty-five years of age in 1935 and is buried in the White Hills Cemetery in Bendigo.

Sometimes a bit of detective work is required to match the photographs. Kee Sing’s photographs clearly match those on file for Louey Ah Sing who was a storekeeper living in Forest Street, Castlemaine in November 1912 when he applied for a CEDT. He was born in Sun Ning (now known as Taishan) in Guangdong province in southern China. He arrived in Melbourne in 1886 where he worked before moving to Bendigo and finally Castlemaine. He made two trips to China prior to this 1913 trip which it seems was his last as there is no record of his return.

Variations in the spelling of Chinese names (which are tonal) and errors in transcribing handwriting can complicate matching records.5 These are all clearly photographs of the same man who applied for a CEDT to travel five times during his time in Australia.

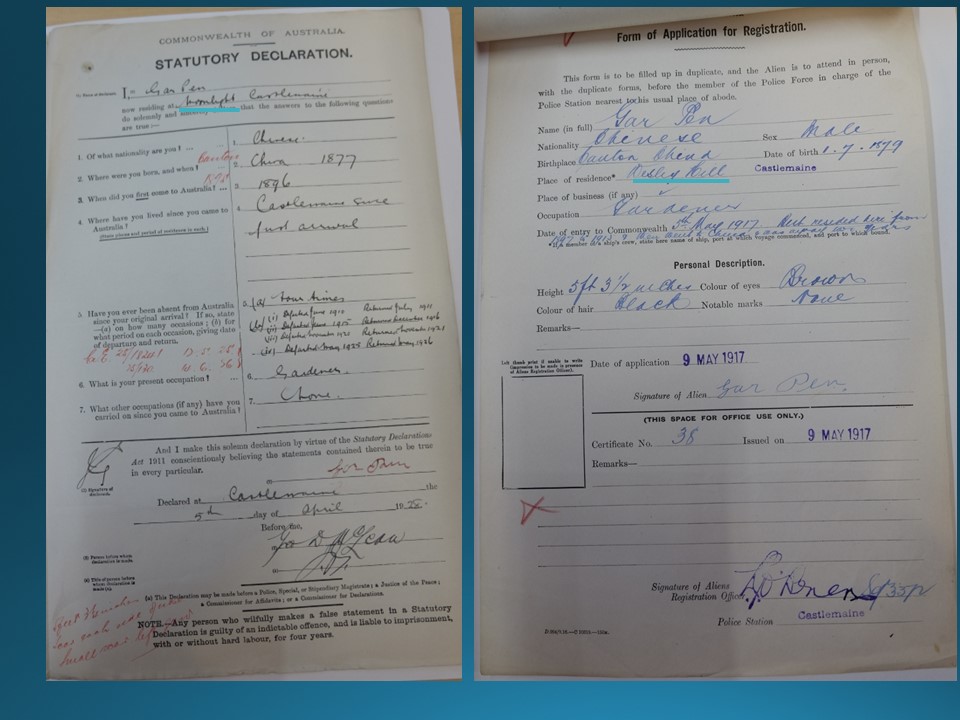

From CEDT application form he completed in 1928 we can see he arrived in Australia in 1896 and lived and worked in Castlemaine as a gardener. In 1928 he was working at Moonlight Flat. His Alien Registration form, however, shows that he’d earlier worked at Wesley Hill. Under the 1916 War Precautions Act anyone who was not a British subject had to register and notify the nearest police station if they changed residence.6

Sometimes it can be difficult to be sure of matches as not all CEDT applications have not survived. The small size of Castlemaine’s Chinese population does make it easier to make some reasonable educated guesses. ‘Toll’ for example is not a Chinese name but ‘Tow’ is and likely refers to the same man. Sing Tow’s name appears in written registers of CEDT applications. The portrait labelled ‘Sing Toll’ was likely used by Sing Tow when he travelled on a CEDT in either 1915 or 1919.

Gock Chee was not identified in all the Verey negatives but surviving photographs show that he is clearly the same man. He arrived in 1920 when he was about twenty-three years old and left Australia in 1923. During this period he worked as a gardener in Castlemaine. He did not apply for a CEDT but likely came on a temporary three year exemption. He stayed at the headquarters of the Ning Yang Society in Melbourne before leaving Victoria. The Ning Yang Society is a community organisation that supports immigration from the region now called Taishan, suggesting this is likely where Gock Chee came from.

Ben Quong Young, who also went under the name Ben Young, arrived in Australia around 1894 in his mid-1920s. We know he initially worked as a hawker because at Christmastime he notified his customers through a newspaper advertainment that in lieu of providing gifts to his customers he was making a donation to the Maldon Hospital,7 He was also reported as making other donations to the hospital.8 By 1916 he is describing himself as a draper in High Street Maldon.9 His photographs were likely taken in 1917 when he sold up his stock to leave the district. He clearly returned again as when he died in 1928 aged 55 years he was buried at the Maldon Cemetery.

I will wrap up now but there is much more I could say about the Chinese Australians in the Verey glass negative collection and more research that could be done about them. Nevertheless the lives of some will likely remain frustratingly opaque.

Most Chinese Australians during this era, like most Australians, led pretty ordinary and uneventful lives. White Australia was also largely uninterested in the activities and achievements of Chinese Australians. Their presence in the historical record can therefore be limited.

As my first slide shows, numerous Chinese arrivals to Australia settled and raised families here but many of those who I’ve featured in this presentation were likely born, married and died in China (or Hong Kong). They worked hard to save money while in Australia to support their families back in southern China. Their family and home was in southern China. Family photographs were taken in China and not Australia. These identification photographs, the product of racist legislation, are precious as they show us the men we would not normally see. Some of these photographs have survived in the archive, but not all. These photographs help us breakdown that amorphous group of men lazily known as ‘Chinese goldminers’ and to imagine them as individuals working in different occupations, with different personalities, living different lives. They help to challenge our preconceptions of what these Chinese men were like.

Castlemaine was built on the discovery of gold in the mid-nineteenth century and its first Chinese communities were established at this time. But all the people whose photographs I have featured in this presentation arrived after the goldrushes. They were mobile, entrepreneurial and many were making sufficient income to make multiple return trips to their families in China. The Verey photographic negatives provide rich evidence of these post-goldrush Chinese Australian communities in Castlemaine.

- Thank you to Ashley Tracy for providing me with high resolution images from his collection for analysis. ↩︎

- ‘Country News’, The Argus, 29 August 1917, p.21, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article1652863. ‘Our Country Service’, Bendigo Advertiser, 31 July 1906, p.3, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article89515766. ↩︎

- For information about the introduction and early use of Chinese identification photography in Australia and New Zealand see: Couchman, Sophie, and Kate Bagnall. ‘Identification Photography and the Surveillance of Chinese Mobility in Colonial Australasia’, Australian Historical Studies, 2023, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/1031461X.2022.2162094. ↩︎

- McKinnon, Leigh and Jack, Anita, A Biographical Dictionary of Historic Figures in Bendigo’s Chinese Community, Golden Dragon Museum: Bendigo, 2015. ↩︎

- Couchman, Sophie ‘Working with Chinese Language When You Don’t Speak Chinese’, in S. Couchman (ed), Journeys into Chinese Australian Family History, CAFHOV: Melbourne, Victoria, 2019, pp.111-128. ↩︎

- ‘Alien Registration forms’, National Archives of Australia, https://www.naa.gov.au/explore-collection/immigration-and-citizenship/alien-registration-records. ↩︎

- [Advertisement], Tarrangower Times, 9 December 1908, p.3, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article267598146. ↩︎

- ‘Maldon Hospital’, Maldon News, 5 January 1917, p.3, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article132756675. ↩︎

- National Archives of Australia: MT269/1, VIC-CHINA-YOUNG BEN. ↩︎