Lockdowns as part of the global Coronavirus pandemic have got many of us looking at our local neighbourhoods more closely and in new ways. Prior to Covid-19 restrictions the ‘scenic walk’ to my local cafe passed through a little neighbourhood park and across a bridge over an open stormwater drain. There’s a folding ladder (wisely padlocked) attached to the side of the drain. The drain itself is a bit too deep to feel you could comfortably jump down into it but wide enough that you could imagine walking along it. It is substantial part of the urban landscape and yet something most people would think little about.

I’ve long wondered where it went. So one day my partner and I walked it, tracking it as we went – from where it starts at Chapel Street, under Nepean Highway up and through to Barkly Street, and then back underground along and down Shakespeare Grove and out to sea at Brookes Jetty (see interactive map below). Rather disappointingly the drain is prosaically called ‘Shakespeare Grove Stormwater Drain’ and previously, even less excitingly ‘St Kilda Main Drain’. Neither really capture its charm or its fascinating history. Research into this drain got me poking around laneways and peering through fences, as well as delving into historic maps and thinking about flooding, geomorphology, water flows and the relationship between the pre-invasion landscape, our evolving drainage systems and how this has all shaped the character of St Kilda’s settlement.

Tracing the drain through time and space

The bluestone lining of the drain got me wondering exactly when the drain had been built. The Melbourne and Metropolitan Board of Works comprehensively mapped Melbourne from the 1890s through to the 1950s to assist them with the construction of Melbourne’s sewerage system. These maps have wonderful detail on them, including drainage.

It is possible to trace the main drain via these maps from Chapel Street all the way to the coast and also southern and northern subsidiary drains that feed into it (visible in the map above). The northern drain is totally enclosed and wiggles its way up under Inkerman Street and Argyle Street where it then runs along Alma Road (today it drains water from along Inkerman Street instead). The southern drain (totally underground when it hits Martin Street) passes under St Kilda Town Hall behind St Kilda Primary School, along Bothwell Street and under the railway line where it gets smaller and smaller until it eventually disappears around the corner of Hotham Street and Oak Grove.

Today the Main Drain is only open from around Chapel Street through to just before Barkly Street (covered in some places and going underneath various roads including Nepean highway). I find it extraordinary, given the price of land in St Kilda, that more of the drain has not been covered over and absorbed into private properties. One local I got chatting to during my explorations admitted that he had been trying to find out, with some difficulty, exactly who he would need permissions from to do just this. These 1890s MMBW maps, however, show that it used to be open all the way to the sea. Various bridges, like the pedestrian bridge I cross on the way to my local cafe, bisected it along the way.

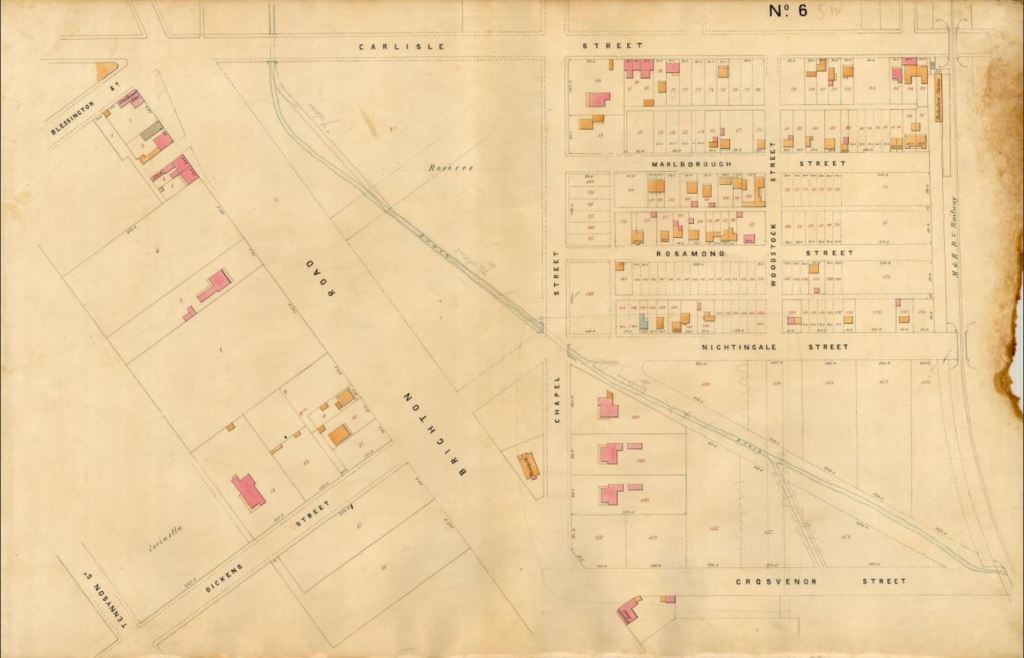

The drain appears on even earlier maps. In 1873 surveyor J.E.S. Vardy drew these plans of the Borough of St Kilda.

See below for southern adjoining map. The drain is coloured blue.

The drain also appears on Cox’s even earlier 1865-6 map of Melbourne but it is not present in Kearney’s 1855 one. Cox’s map also clearly shows the path of the southern subsidiary drain, under the railway line and beyond. But not the northern subsidiary drain.

Understanding the drain’s geomorphology

As I was tracking the drain on earlier and earlier maps I was also looking to confirm whether it had it origins in an early stream of some description just as nearby Elwood Canal is an extension of Elster Creek. Kearney’s 1855 map clearly shows that land where the drain was eventually constructed is undeveloped but there is no feature marking a river or stream or even swampland.

So I started thinking about the shape of the land and how water might have flowed across it. I turned to modern topographic maps to investigate this. From the map below you can see that the drain is ideally placed to capture run-off from the the rise that runs east-west across the top of the map and also from the small rise which is the location of the St Kilda Botanical Gardens.

Chatting with a friend whose son attends St Kilda Primary School, she told me that the school oval, which lies above the southern arm of the drain, regularly floods when there is heavy rainfall. In fact there is a drain cover just off the oval where you can look down into the drain.

Water flows and flooding shown in the map below confirms my friend’s observation. It illustrates a 1% flood. This means that there is a 1% chance of a flood of this size happening in any given year. You can clearly see flood water movement into and around the main drain and what I’m calling the southern subsidiary of that drain. The school is marked with an ‘S’ in a triangle. I’ve since rushed down to the Main Drain after a sizable downpour to assess the significant rise of water in the drain.

As part of understanding of the geomorphology of the area and thinking about what it might have looked like prior to colonisation I also turned to geological maps. Melbourne sits atop a layer of volcanic basalt from which bluestone was quarried and used from as early as the 1830s to construct many of its streets, lanes and drains. The drain itself runs neatly through a Quaternary (Recent) deposit of fluvial (or riverine) sedimentary rock and that the rise from which much of the drain’s water flows from is an outcrop of very early Silurian (Upper) sandstone and siltstone. This green fluvial deposit is of a similar age to deposits around the Elwood canal/Elster Creek which supports the idea that in recent geological time there was a stream of some description in the area currently occupied by the drain.

Green (Qra) areas: Quaternary (Recent) riverine deposit.

Other Green/blue areas (Qrp, Qrs): Quaternary estuarine deposits

Yellow areas (Tpr): earlier Pliocene ‘Red Bluff Sand’

Grey (Sud) area: Silurian (Upper) sandstone and siltstone.

John Butler Cooper’s A History of St Kilda published in 1931 is a wonderful history, very much of its time. It describes a creek that ‘threaded the land’ now occupied by St Kilda Town Hall. He also provides a verbose and challenging to understand description of the original topography and water features in the area of the drain. He describes the area on the south side of ‘St Kilda Hill’ with its apex at Alma Road and Nepean Highway of once having ‘its creeks, now a large city drain’. But he does not describe in any detail the route of any of the creeks he refers to but does note in passing that the Main Drain roughly followed the path of ‘an old creek’.

In Gary Presland’s The Land of the Kulin: Discovering the Lost Landscape and the First People of Port Phillip, Presland does not describe the particular area of the drain in any detail but say that the area to the east and south of the Yarra River was ‘covered mainly with a low woody scrub’. On the higher ground between Chapel Street and Nepean Highway was ‘thick wattle forest interspersed with mature gums’, like the Corroboree tree that still stands at St Kilda Junction. The scrub was about a metre high and grew closely together and was adapted to the dry conditions ’caused by the poor drainage of the underlying soil and the small number of permanent streams’.

A small publication written by Meyer Eidelson for the City of Port Phillip, Yalukit Willam: The River People of Port Phillip, refers to the site of the St Kilda Town Hall (through which the southern subsidiary of the Main Drain runs) as previously being a wetland site and popular camp place for the Yalukut Weelam people. The book claims ‘water was supplied from a creek flowing down from St Kilda ridge (near St Kilda Cemetery)’ to the site. It also says that the creek (actually the drain) can still be viewed through a trapdoor in one of the rooms of the Town Hall. While I’ve not been able to view the drain at the Town Hall myself I have been able to confirm its presence with the Council and spoken with someone who has – Isaac Herman.

I was introduced to Isaac by the Kay Rowan from the Port Phillip Heritage Centre when I approached them about further information about the drain. Isaac is an amateur historian who has been researching the City of Port Phillip’s historic drains and lost waterways for many years, in particular the history of Elwood Canal. He has traced the location of two of at least three natural freshwater springs in St Kilda. One of which he believes probably still flows down Alexandra Avenue, along Inkerman Street and into the Main Drain. He also told me that he had been in touch with a naturalist who found native plants and invertebrates still thriving within the Main Drain!

Constructing the drain

After exploring the Main Drain through St Kilda’s backstreets to the sea I began seriously delving into its history. I was delighted to also find it’s origin story discussed in my copy of John Butler Cooper’s A History of St Kilda. This is a monster two volume history published in 1931 but it is a municipal history at its fineness providing great detail about the construction of public amenities in the area, including the St Kilda Main Drain. Cooper described how when Crown Land was sold, allowance was not made for drainage and so when the St Kilda Council began constructing drains they had to notify landowners and provide some recompence. On 5 December 1857 the Council’s Town Clerk published a notice in the Age notifying affected property owners that they were about to commence ‘draining the low lands of the municipality’. Plans were available at the St Kilda Court House for affected property owners to view.

In the text ‘High-street (Brighton-road)’ is now called ‘Nepean Highway’ and ‘Beach road’ now called ‘Carlisle Street’.

The council had been urged to action in April earlier that year by a petition from around 77 local residents calling for the existing ‘channel’ to be narrowed and lowered in order to better carry off water. The area around what is now Nepean Highway and Vale Street was colloquially called ‘the swamp’ and they argued that it was ‘most injurious to the property and health of the inhabitants’. James A Hannon also noted in a letter to the council that year that a drunken man had drowned in the drain and that accumulated water was damaging the foundations of his and other houses in the area. A surveyor was sent to evaluate the area west of Nepean Highway in May that year. He found it requiring ‘most necessary work’ and noted in particular that the area ‘south of Inkerman road [now Inkerman St]’ was

'a large swamp, which after continuous or heavy rains receives the washings of the upper ground, and which, as well as the offensive condition of the low streets in the locality cannot fail to exercise a prejudicial effect upon the health of the inhabitants of this portion of St Kilda'. (St Kilda Historical Correspondence A-Z, D21: May 1857 Central Board of Health report by its Inspector of absence of any system of drainage of lands west of Brighton Road (High Street) from the Junction southwards)

He criticised other areas where swine were kept in ‘objectionable conditions’, ‘offensive drainage’ flowed from the various butchers in the area and manure and other refuse including dead fowl allowed to accumulate.

Although construction of the drain as far as Barkly Street commenced in December 1857, according to Cooper, by September 1861 residents in the ‘low lands of St Kilda’ had been ‘frequently’ pressing the Council for work to be done on the Main Drain as they were regularly flooded out ‘in the time of winter and heavy rains’. Another petition was sent by ratepayers from the Vale Street, Carlisle Street, Nepean Highway and Martin Street area in 1863. They complained that the existing drain was rapidly and continually filling with sand from East St Kilda and they were worried that the area would flood again in the ‘wet season’.

The Council then decided to construct the portion of the main drain from Acland Street to the open beach, presumably joining the two sections of the drain together. The first section of the drain was completed in March 1862 and after a contribution of £2,300 by the Victorian government in 1864, the full drain was completed in 1865 to the ‘Council’s most sanguine expectations’.

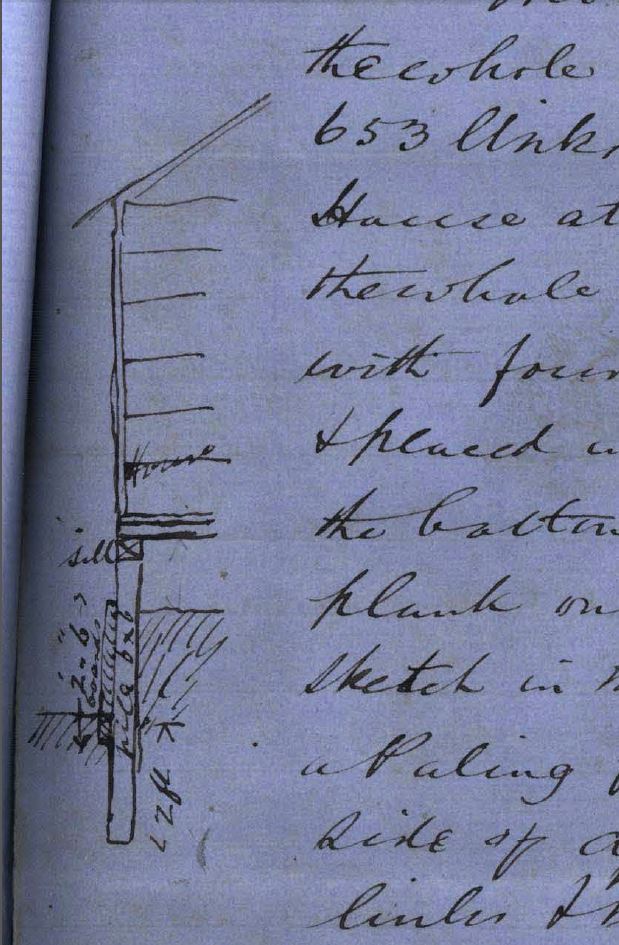

The original tender documents for both the construction of the first stage of the drain in 1858 from Chapel Street to Barkly Street and then, in 1861, the final section of the drain to the sea which also included deepening the earlier section of drain are held by the City of Port Phillip Records Service. These documents include a sketch of one of the bridges built over the drain and also details how the drain should be lined with bluestone (with no honeycombing) tucked and pointed with Portland cement.

According to Cooper the Main Drain’s southern subsidiary drain, that passes St Kilda Town Hall and through the grounds what is now St Kilda Primary School (formerly Brighton Road Primary School) was completed in 1881 but an earlier version of this drain already appears on Cox’s map in 1866.

Living with the drain

The history of St Kilda Main Drain is also a reminder of how the shape of the landscape and the way water flows over and through it shapes the nature of settlement. Drainage plays a significant role in this process. Kearney’s 1855 map shows a noticeable absence of settlement in the area where the drain was eventually built. My first thought was, ‘oh that was convenient’, but of course this is no coincidence. The topography of the area shows that surrounding water would all have flowed into the area where the drain was built. While it might not have been marked as a ‘swamp’ it would no doubt have been pretty boggy land, particularly in winter or after heavy rain.

The wealthy of St Kilda (and indeed elsewhere in Melbourne) built on Melbourne’s hills and rises. Walking the area from the rise at St Kilda Junction down the slope to St Kilda Town Hall, with an eye on the nineteenth century architecture, you walk from the large brick mansions of St Kilda’s wealthy class down to the small wooden cottages of the commercial and working classes or ‘cottagers’. The area around Inkerman Street and the St Kilda Town Hall triangle was colloquially known as the ‘Balaclava Flat’.

In the 1880s Balaclava Flat was known for its criminals, ‘low’ or ‘objectionable’ characters, drunken assaults, ‘disorderly houses’ and their support for the Labor Party! In 1883 the area still did not have running water. As Cooper put it in his history of St Kilda, ‘naturally the men on the hill were seen from a greater distance than the men who dwelt upon the flat’.

The stark class differences are lain open in a memorial submitted to St Kilda Council on 8 February 1875 signed by 211 outraged ratepayers on ‘the hill’. They were complaining against the Council’s decision to relocate the post office from the corner of Alma Road and High Street (now Nepean Highway) on the St Kilda ‘hill’ to the corner of Inkerman Street, ‘the flat’. The Council had selected the new location based on the fact that it was centrally located within St Kilda’s population. The memorialists argued not all of St Kilda’s population used the services of the post office equally.

‘...we, the undersigned burgesses of St. Kilda, beg respectfully to submit, for your consideration, the hardship, and injustice, involved in this arrangement with the principal inhabitants of St. Kilda viz. – to those who reside on the hill parts, to whom it would be very inconvenient to go so far as the Flat, either to transmit messages, or to post letters. We beg, therefore, in the first place, to call your attention to the fact, that almost the entire of the business of the Telegraph, and Post offices, of St. Kilda lies with the residents on the Hill portions of St. Kilda. The Cottagers, who reside in that portion of St. Kilda, known as “The Flat” seldom, if ever, require telegraphic communication. For proof of this, we beg to refer you to the statistics of the St. Kilda Telegraph office.’ (Quoted in J.B. Cooper, The History of St. Kilda 1840-1930, vol.2, Printers Proprietary Ltd: Melbourne, 1931, pp.112-113)

Given the distance between the old and new post office is only about 500 meters, the memorial also highlights the importance, even for St Kilda’s wealthier classes, of walking as a means of transport.

Aspersions were again cast on the people living on the Balaclava Flat in 1887 in a dispute about the site for the new St Kilda Town Hall. The Council had set aside land on the Balaclava Flat which was currently being used as a rubbish tip and municipal storage yard. This displeased those on ‘the hill’ who wanted it located near the corner of Alma and High street. Others also wanted a third location. A public vote was held regarding the three sites with the current site on the Balaclava Flat winning. Fortunate, given the Council had already reserved the land for this purpose!

While the construction and then deepening of the drain no doubt improved the quality of the land for occupants in the area it was still not the most salubrious of environments to live in. In 1869 one newspaper correspondent described walking near it as like ‘swallowing a violent emetic’ and warned that ‘it is just the place for fever to breed in, and for cholera to fasten on, and gain vigour, and spread from’. The following year there was passing mention of ‘very dirty sewerage’ discharging into the sea near inhabited parts of St Kilda beach.

John Green, a plasterer of Little Bourke Street, seems to have discovered in 1871, rather belatedly given construction of the drain happened 1858-1861, that a property he owned which fronted onto Albert Street (located between Barkly Street and the sea) could no longer be accessed due to the open drain. He wanted access to Council documents and compensation. A few months later he complained that, without his permission, the council had taken a portion of his land and built a wall on it as part of enclosing the main drain. He got lawyers involved and sought damages of £100 and then compensation of £45. It’s not clear what recompense he got, if any. The Council seemed to eventually decide he was a vexatious litigant and agreed to inform him that ‘they decline to enter into any arbitration in his case, and must leave him to take any steps he may think fit’.

While today the drain is only open between Chapel Street and Barkly Street (except where it passes under roads), it was previously largely open with bridges crossing it and seems to have been progressively covered over. A letter to the Prahran Telegraph in 1904 complained about the fact that the southern arm of the drain was open as it ran through the grounds of what is now St Kilda Primary School. Again we see class differences within St Kilda’s community revealed. The correspondent wrote that the

‘portion which runs through the State school’s grounds – is neither cemented nor tarred. So different from the portion under the Town Hall, which is effectively arched over in brick and cement. What is good for the corporation should be beneficial for the poor school “kiddies,” who daily play and eat their modest lunches over a noisome sewer, which is neither tarred, cemented nor covered‘. (‘Council voices’, The Prahran Telegraph, 9 April 1904, p.3)

The 1897 Melbourne Metropolitan Board of Works map (see above) shows the drain underground in a ‘colvert’ before becoming a ‘pitched channel’ on the school grounds with two bridges over it giving children access to the school building from Chapel Street.

Class divisions are again revealed in the final account I located about lives of those living in the area of the drain. During World War II wealthier St Kilda residents, anxious about possible Japanese bombing, constructed bomb shelters. The government also provided public trenches. Building your own shelter close to home was not viable for all. Mrs A Green of 361 High Street, St Kilda wrote to the Town Clerk in February 1942 on behalf of residents near Blanche and Vale Streets asking for modifications to the Main Drain so that it could be used for shelter in case of bombing:

‘…all our yards are too small to put in slit trenchers (sic) if you are willing would you kindly fix up fences of the drain facing the lanes and roads by making them into gates to be easily opened at a minute’s notice and also to put down a few steps at each entrance so as the aged people would not fall and get hurt‘. (Quoted in A. Longmire, The Show Goes On: The History of St. Kilda, Volume III, 1930-1983, Hudson Publishing: Hawthorn, p.95 originally from St Kilda Town Hall Archives)

Even today, the area around the Main Drain between Chapel and Barkly Streets is a bit a mish-mash. There are smart gentrified houses and modern apartment blocks but also pockets of old warehouses and light industry and the area between Nepean Highway and Barkly Street is notorious for its street prostitution. The drain is well decorated with street graffiti and tags of various styles, but it doesn’t smell anymore. While I was exploring and photographing the area, a local resident approached me, anxious to know what I was doing. Concerned, I think, that I was casing his place. The area of the drain on the beach-side of Nepean Highway is still an area of dubious reputation – an area of streetwalkers and drug dealers mixed with middle class gentrifiers and old timers. We got to talking. His house backed on to the drain and he had lived there for many years. He’d seen it used as a place to deal drugs and a get-away route by those fleeing the police. He had also experienced the drain flood on numerous occasions. He told me about an elderly neighbour who had lived there much longer than him who had compiled a photograph album filled with photographs of the drain in flood dating back decades. Sadly when he asked after it after her death it was nowhere to be found. I can’t help hoping it is still out there, somewhere, waiting to be discovered.

The drain in flood

The irony of the St Kilda Main Drain or Shakespeare Grove Main Drain as it is known today is that it STILL floods. Quite regularly. According to Isaac it probably floods every 10 years or so with notable flash flooding on average, since colonisation every two years. Isaac Herman was told by a council worker about a major flood in 2011. The worker was marooned on a ledge outside the library. The underground car park and basement were entirely submerged with water and along the street they saw floating car and even a fire engine drift past.

(Image forms part of a collection of flood images photographed by City of St Kilda residents and council officers on 2 February 1989

Port Phillip City Collection, b/w photograph. sk2828.3)

The hard and impermeable surfaces of cities speed up the flow of water as it cascades off roofs, down drainpipes, off roads and footpaths. It actually makes flash flooding more likely not less and causes additional problems with pollution as drains channel polluted water very quickly into the bay. As Isaac notes giving us ‘perhaps the worst environmental outcome you could opt for’. Climate change poses other challenges. It is anticipated that we will see an increase in the intensity of storms which means that we need systems to be able to move or absorb large volumes of water. So civic engineers today are introducing soak pits and constructing wetland sinks to slow down the flow of water and create buffers that can absorb and filter it. In fact works are in progress to recreate the pre-colonial wetlands around the section of Elster Creek (which becomes the Elwood Canal) that runs through the old Elsternwick golf course for just these kinds of reasons.

What started off as idle curiosity about a local drain has really changed the way I see the city. Browsing some of the websites of Melbourne’s urban explorers, such as the Cave Clan, also gives you the chance to view the extraordinary world of drains that the lie under our feet. But I also have a much greater appreciation of how drains shape our built environment and also its character. But what has been most wonderful is the window that they provide into our pre-colonial landscapes. I will never look at a drain cover the same way again.

For more history on the St Kilda Main Drain have a listen to my podcast published as part of the My Marvellous Melbourne podcast series.

Sources

Cooper, J.B., The History of St. Kilda 1840-1930, vol.1, Printers Proprietary Ltd: Melbourne, 1931.

Cooper, J.B., The History of St. Kilda 1840-1930, vol.2, Printers Proprietary Ltd: Melbourne, 1931.

Eidelson, Meyer, Yalukit Willam: The River People of Port Phillip, City of Port Phillip: Melbourne, 2014.

Longmire, A., The Show Goes On: The History of St. Kilda, Volume III, 1930-1983, Hudson Publishing: Hawthorn, 1989.

Presland, Gary, The Land of the Kulin: Discovering the Lost Landscape and the First People of Port Phillip, Penguin Books: Ringwood, Victoria, 1985.

Trove newspapers, various, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper.

St Kilda Historical correspondence A-Z, City of Port Phillip Records Archive.

‘Quarries and brickmaking‘ and ‘Water supply‘, e-Melbourne website.

Maps

Henry Laird Cox, Map of Port Phillip, surveyed 1864 and published 1866, State Library of Victoria.

James Kearney, Melbourne and its suburbs, 1855, State Library of Victoria.

J.E.S. Vardy, Plans of the Borough of St Kilda, 1873, published by Hamel & Ferguson, Melbourne, City of Port Phillip heritage collection.

Melbourne and Metropolitan Board of Works maps, State Library of Victoria.

St Kilda & Balaclava Flood Awareness Map, from Balaclava and St Kilda Local Flood Guide, September 2018.

Topographic map of Melbourne, Topographic-map.com.

Victorian Geological Survey, 1974.

I’m very grateful to Isaac Herman for generously sharing his research and knowledge about the Main Drain and its prehistory.

Following hidden drains is really fun.

I live near the middle reaches of the former Elster Creek, and it’s interesting to find the clues of the modern drain.

Its course can be traced by odd shaped house blocks that mar the strict rectangles that otherwise rule, and the fact that the owners aren’t allowed to build over the top.

About eight years ago, they (probably Melbourne Water) replaced the bridge under one of the more important roads. You wouldn’t have known before that a bridge existed at all, but when the road was ripped up you could see the bluestone abutments of the original bridge, much narrower than the modern road. On either side there were concrete extensions provided to widen the bridge to the full width of the road. They replaced the concrete bridge with a culvert, so it is now all buried in concrete and will never be seen again. Well, almost all. The southern footpath is still a bridge, and on the outer edge the curb, complete with sockets for the former wooden railing, still exists. Beyond the creek has been covered by the forecourt of a garage and you wouldn’t know that it exists.

The most fugitive clue of the creek was briefly revealed a couple of years ago in the depths of the drought. The creek runs through a modern park with nary a clue to show that it is there. But there isn’t much soil over the top of the drain, and during the drought the grass over the drain died back, while the grass on either side remained greenish. The course and extent of the modern drain was revealed in the dead straight run of yellow grass through the park.

That’s fascinating! I was inspired to walk some of Elster creek too now keen to go and look more closely

Someone (perhaps Gary Presland) described early St Kilda as an island surrounded by swamps in every direction, and certainly the crucial events in its early history often involved questions of drainage. It’s important to note the consistent position of St Kilda Council, that it required State Government funding to deal with the issue, as a high proportion of the storm water that flowed through St Kilda originated in Prahran and Caulfield. (see DEPUTATIONS. (1866, September 19). The Age (Melbourne, Vic. : 1854 – 1954), p. 6. Retrieved August 5, 2019, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article160216457)

An underlying problem was that sand dunes formed a ridge along the sea coast and there were few streams or other outlets, except in times of serious flooding. Elster Creek was one outlet, though criticisms of the council abattoir located in Barkly Street on the north bank of the creek often pointed to the lack of flow to carry away offensive material. I’ve searched a bit for any reference to a creek following the course of Shakespeare Grove, but without success. There was a bridge in Acland Street, but there’s no reference to it before the digging of the drain.

The battles over the siting of the Post Office and the new Town Hall were the continuation of a fight that started in the 1860s. The original commercial centre of St Kilda was around the Robe Street/ Grey Street corner (opposite the first Town Hall), but by the 1860s an alliance of the High Street traders and the silvertails of East St Kilda was trying shift the centre of services to the Alma/ High corner. (I’m working on a piece about this, probably for the St Kilda Historical Society web site.)

I’m curious about your statement that the Balaclava flat didn’t have running water till 1883. This seems unlikely – can you provide a source?

Finally a few comments on Cooper’s history. It contains some fascinating information, but it’s not possible to trust any of his “facts” unless you can find confirmation elsewhere. As an historian, he was a good journalist, who seemed to have preferred the interesting anecdote to serious research. I’m currently reading it carefully, and here are two examples::

Page 7 – James Duerdin, “In the year 1850 he owned the Prince of Wales hotel, in Fitzroy Street…” Princes of Wales was built in the late 1850s by William Kesterson, and it remained in the ownership of his family till the 1930s. (Duerdin in fact built the Esplanade Hotel in the 1870s.)

p. 84 List of original St KIlda councillors: “Alexander Sutherland was a machinery merchant in Melbourne, who later on built a large house in North Road, Brighton, where he died in the year 1911.” This Alexander Sutherland did not arrive in the colony until the 1870s. The original councillor was Alexander Sutherland, builder, of Acland Street, who died in 1860.

I have found many, many more examples scattered through the two volumes.

I’d love a chance to talk to you, perhaps over coffee if we are ever allowed to do that again!

Hi Ken, Thanks so much for your comments really interesting to learn more about some of the historical context you provide. It would be wonderful to catch up over a coffee and learn more. So perhaps I have perhaps misunderstood the newspaper report about the running water. It was a report in ‘The Telegraph, St Kilda, Prahran and South Yarra Guardian’, 15 Sept 1883, p.7. Cr Balderson was requesting that the Yan Yean be extended to the streets on the Balaclava flat before the summer set in. Best Sophie

Just goes to show that class prevails! I knew that the laying of water pipes in St Kilda began at the end of 1861 (http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article57083280), and hadn’t appreciated how long it was before such an essential service was extended to the rest of St Kilda. Strikingly, pipes were laid in Orrong Road (Alma to Carlisle) by 1876 (http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article109631907).

By the way, have you seen the maps at http://handle.slv.vic.gov.au/10381/123955, which provide useful descriptions of vegetation, topography, etc.?

That really is interesting. Class does indeed prevail! I wonder how long it took to run the pipes once the issue was raised in council?

And yes, that 1857 map is a beauty. I came across it later in my research (via Isaac) and really should have worked it in. And I agree. I’m not convinced it was a ‘creek’ as such, or if it was then highly intermittent. Your point about the sand dunes is one I hadn’t fully appreciated. That 1857 map certainly shows that there was plenty of wetlands to form the drain.

Sophie,

Just following up on my point re sand dunes restricting the flow of water into the Bay – here is an indication of what became of those dunes:

TO Carters-WANTED two or three Loads of good SHELL SAND from St. Kilda, delivered at Richmond. Address, stating price, to Sand, office of this paper.

(Advertising (1857, September 23). The Argus (Melbourne, Vic. : 1848 – 1957), p. 8. Retrieved November 13, 2020, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article7139157)

One of the fascinating parts of this project is not just discovering what remains of our past landscape but also, as you point, how much it has been reshaped and changed.

Hi. Thanks for a fascinating read. I’ve often wondered about that drain.

There is another drain which runs from Alfred Place (behind Robe St) under the alleys linking Clyde, Fawkner and Havelock Sts through to the reserve on Barkly St. Presumably it also joins the Shakespeare Grove drain.

How interesting! Will have to see whether it shows up in the early maps

Not exceptionally relevant but there is a tiny hidden rivulet running underneath a property on the corner of Duke and Chapel Streets in Prarahn, only a (very forceful) stones throw from Balaclava. It is accessible through a small trapdoor in a cramped storage room. It all sounds very Enid Blyton, but I always thought it would be fun to follow its course.

That sounds super intriguing. This map might help trace it – http://handle.slv.vic.gov.au/10381/122078.

A great read. I’ve spent a few summer days wandering through these canals & tunnels.

Here’s a video we shot many years ago.